The Tang Hengdao: China’s Lost Sword of Empire

Introduction: The Blade That Built an Empire

Standing straight as a pine tree and sharp as a calligrapher’s brushstroke, the Tang Hengdao (唐横刀) was the ultimate status symbol of China’s golden age. Unlike its curved descendants, this double-edged straight sword embodied the unyielding spirit of the Tang Dynasty (618–907 AD), when Chinese warriors stood toe-to-toe with Turkic horsemen and Tibetan cavalry – and won.

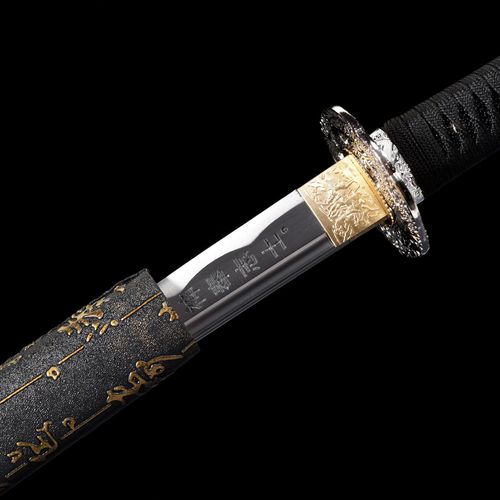

At LOONG BLADE, we’ve resurrected this imperial masterpiece through years of archaeological research and traditional forging, offering modern collectors a chance to own the sword that defined East Asian warfare.

Chapter 1: Anatomy of an Imperial Weapon

1. The Straight, Double-Edged Design

- Length: 70–110 cm (shorter than European longswords)

- Cross-section: Rhombic or hexagonal for maximum rigidity

- Balanced weight: 1.2–1.8 kg (perfect for one-handed use)

Why straight? Designed to pierce lamellar armor (扎甲) in disciplined infantry formations.

2. The Secret Metallurgy

Tang smiths perfected baijiangang (百炼钢) steel:

- Folded 100+ times to remove impurities

- Sandwich-construction: Hard steel edges with softer iron core

- Quenched in animal blood (per Tang Dynasty records) for shock absorption

Modern tests show comparable hardness (HRC 58-60) to Japanese tamahagane steel.

Chapter 2: Battlefield Dominance

The Weapon That Conquered Eurasia

- 751 AD Talas River: Tang infantry held line against Arab cavalry for days

- An Lushan Rebellion: Hengdao-equipped Mobei Army became dynasty’s last hope

- Japanese Adoption: Proto-katana (直刀 chokutō) evolved from captured hengdao

Tactical Advantages:

✔️ Thrust-friendly point for anti-cavalry use

✔️ Double edges allowed slashing in crowded formations

✔️ Compact size ideal for mounted troops

Chapter 3: Cultural Iconography

The Sword of Status

- Officers’ models had jade pommels and gold-wrapped hilts

- Civilian versions (文剑) featured poetry engraved on blades

- Tomb guardians: Many Tang elite buried with hengdao as afterlife protectors

Artistic Legacy:

✍️ Featured in famous Tang poetry like Li Bai’s "Drawing my sword, I cut flowing water"

🎨 Depicted in Dunhuang murals held by armored generals

Chapter 4: Why Did It Disappear?

The Great Shift to Sabers

- 10th century: Cavalry warfare favored curved dao

- Song Dynasty: Armor-piercing role replaced by polearms

- Cultural shift: Scholarly jian became favored over military hengdao

Last Survivors:

- Japan’s: Straight tsurugi swords preserved Tang techniques

- Tibetan: Some ceremonial swords retain hengdao proportions

Chapter 5: LOONG BLADE’s Modern Recreation

Using Tang Dynasty manuscripts and excavated relics, we’ve rebuilt the hengdao with:

Traditional Methods:

- Ancient ore smelting: Using Zhejiang iron sands

- Layered construction: Visible in X-rays like originals

- Authentic fittings: Turquoise-inlaid crossguards

Modern Testing:

⚔️ Cuts cleanly through bamboo armor replicas

🛡️ Deflects simulated arrow impacts without bending

Conclusion: The Sword That Never Died

Though absent from modern wuxia films, the hengdao’s DNA lives on in:

- Japanese katana forging techniques

- Korean ssanggeom dual swords

- Vietnamese emperor’s ceremonial blades